I made my first beer in November. I initially toyed with the idea last spring, reading about the process, and drawing up a list of preferred styles. But then I ordered my camera, and decided I couldn't afford both. I started with a kit instead, albeit a good-quality one, and was pleased with the results. I didn't quite follow the standard practice, in fact - I performed both fermentations in the same container, a pressure barrel, since I didn't want to pay for a separate fermenter at the time. I transferred the beer into sanitised buckets, before returning it to the barrel for the second fermentation after I'd cleaned it. The result, from Woodforde's Norfolk Wherry kit, was good - red-brown, fruity, smoothly carbonated, and very drinkable. Whether it was strong I can't say - I didn't measure the relative densities, but I didn't get particularly drunk even after several pints, so maybe it didn't ferment all the way. Nonetheless, it was a good enough experience to persuade me to revive my original plans, so once Christmas was out of the way, I set to finding a recipe, and giving it a name.

There are thousands of recipes online, and for a beginner it is very hard to determine which is best, and what the differences are. I found one that sounded interesting, then tried to obtain the ingredients. Since it was an American recipe, I had to make one or two substitutions, which means this will be effectively unique, and so I feel I can give it my own name.

The original recipe can be found here. It's an unusual hybrid that combines "the color of an American Brown, the caramel notes of a Scotch Ale, and the hopping regiment of an India Pale Ale", according to the brewer. I had particular difficulty sourcing the hops, and decided to reduce the bitterness a little, as I prefer a slightly sweeter brew.

Here's the recipe. It's converted to metric, which will be easier for me to measure with the equipment I have:

Old Margery's Winter Ale

20.8 litres (a little over 36.5 UK pints)

grain bill

5.443kg Maris Otter malt

340g amber malt

227g English crystal malt

227g chocolate malt

155g light brown sugar*

72g white sugar*

57g roasted unmalted barley

hops

28g Warrior (a very high alpha acid US hop)

14+28g Admiral (a substitution for the Vanguard that was unavailable)

yeast

Wyeast Ringwood Ale (1187)

*I needed dark brown sugar, but couldn't get any wherever I looked in my town - so I used what I had.

method: in theory

The Warrior and 14g Admiral hops will be boiled for 60 and 20 minutes respectively, the remainder being added to the hot wort post-boil. The method I'm going to use for mashing is intended to require as little specialist equipment as possible, so might sound rather unorthodox, but I'm hoping it won't ruin the finished beer. I'll use my stock pot, which I'll pop into the new oven, which can hold a good temperature, between 60 and 70 C (I'll see if I can fine-tune it further). I'll strain it using a chinois and muslin, which seems more manageable than the usual homebrew techniques, especially given my lack of a second large container. If I need to cool the wort, I'll just plunge the pan into a sink of iced water - again, I'm not investing in anything more fancy until I am better acquainted with the process.

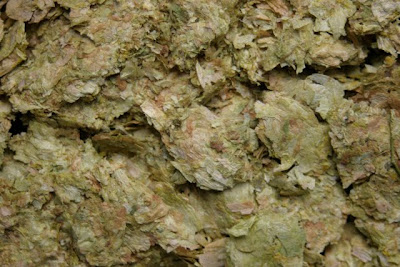

Dried Warrior hops. They're flattened because they were vacuum-packed; when rehydrated, they look similar to fresh hop cones. They smell wonderful - the closest I can think of is juniper berries.

Dried Warrior hops. They're flattened because they were vacuum-packed; when rehydrated, they look similar to fresh hop cones. They smell wonderful - the closest I can think of is juniper berries.method: what happened

So it took much longer than I was expecting, precisely because the capacity of my pan was much less than I thought. I mean, I knew what it was, but the grain swells up, and you sparge (rinse) it with lots more water than I realised, so I ended up doing a continuous multi-batch process, with one smaller pan in the oven (which held the correct temperature well), and the larger stockpot boiling the wort with the hops. It took from 5pm to 1am the first day, which was about half the total, then I restarted 1pm the next day, finishing mid-evening. Luckily, I found it enjoyable, not too stressful, although it did make the most awful mess of anything I've ever done in the kitchen (think sticky brown liquid spilled on the floors, hob, worktops, and lots of washing up). Sadly I broke the new hydrometer I bought, by dropping a mortar on it (I was using the granite mortar to weigh down the grain and extract as much liquid as possible). I've tried weighing the wort to see what the gravity is (in order to work out how much sugar was extracted, and how alcoholic the finished beer will be), but it will be inaccurate. Incidentally, I didn't bother with muslin - it wasn't necessary.

Using the excellent brew calculator at Beer Calculus, I've determined it should be 6.4% abv, with a bitterness of 47.6 IBU (so fairly bitter), and dark brown to black in colour: a good hearty brew for winter. I've saved a lot of beer bottles, because I don't want it hanging around in the keg for too long, since I may want to do another batch of something fairly soon, and hopefully it will keep longer in bottles.

Update: fermentation

I was worried that the yeast was dead. It comes in a large sachet, that you strike to break an internal pack, and then it's meant to swell up. Well, mine didn't, not even by the next day. So I poured it into a sterilised jug, with some boiled wort and a little sugar. The following day (when I was ready to add it to the main batch, there was still no sign of life. I added it anyway, but contacted the shop who'd sold it to me. They didn't seem concerned, but were very helpful.

The following day, there was a hiss on opening the barrel lid - something was happening. The day after, it had taken off. Indeed, it was such a violent fermentation that I couldn't fully unscrew the lid for a whole day. I researched the yeast online, and found it was often slow to start, but also that it needed high oxygen levels - and that professional brewers use open fermentation vessels to provide that. Once the pressure died down, I left the lid on, but unscrewed, and regularly swilled the liquid around, to reoxygenate it, and prevent too much carbon dioxide buildup.

After around ten days, the fermentation has died down, and I'll set to bottling it in the next week (this yeast produces a lot of diacetyl, a chemical that smells of butter, so it is recommended to rest the beer after fermentation, to allow that to dissipate - buttery notes may be welcome in certain white wines, but apparently hardly ever in beer).

Update 1st February 2012:

I haven't got round to bottling the beer yet, for the simple reason I can't afford to buy a bottle capper yet. It should come to no harm in the sealed fermentation vessel - and some of the buttery notes the yeast has produced will die down. I measured the final gravity as 1.010, which means the alcohol by volume is around 6.7% - slightly stronger than originally predicted. It's rich, complex, bittersweet, and not terribly drinkable just yet.